As a UX Designer with a natural curiosity, I enjoy working with people from different backgrounds. Nowadays, it is almost impossible not to work with different cultures. We are all interconnected; teams include different cultures within or across countries.

Like cross-functional teams, multicultural teams are a huge driving force for innovative thinking. Bringing different perspectives together allows us to learn from each other and to learn more about ourselves.

I recently read The Culture Map by Erin Meyer. I highly recommend her book to everyone who works in an intercultural environment. I could relate to many of the stories in this book: I have lived in three different cultures (Germany, Switzerland, and Canada), one of which is a cultural melting pot (Canada is a mixed bag of so many nationalities to me).

Erin Meyer, a professor at a French business school, identified 8 behavioural patterns that describe cultural differences. Of course, these are simplifications like all patterns, models, and behavioural concepts. We are not just the result of our cultural background. But Erin’s collection contains some great insights that help us describe and, therefore, improve intercultural communication.

In this article, I share my key takeaways and their application to teamwork in the design process.

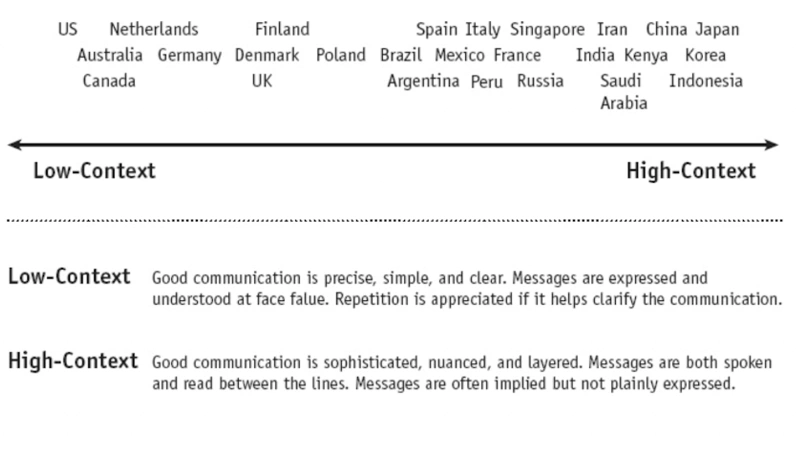

Communication style: implicit vs explicit

Communication is one of the key factors for good teamwork. How do we ensure that the messages we send are being understood correctly?

Some cultures express their messaging very explicitly (low-context cultures). They aim to be as clear and simple as possible. I quite enjoyed this when I moved from Germany to Canada: Whenever a complex topic is shared (in books or in a presentation), the structure of the message is always aimed at being easily understood, following the formula: ”Tell them what you are going to tell them, then tell them, then tell them what you’ve told them.”

Other cultures are less explicit and require the receiver to read between the lines (high-context cultures). For me personally, this often shows in understanding sarcasm or each other’s sense of humor. The less “context-focused” we are, the easier it will be for us to miss certain cues to understand a message correctly.

? Communication style: the cultural scale

Cultures with a highly explicit communication style are the US, Australia, Canada and the Netherlands.

Cultures with a highly implicit communication style are Japan, Korea, Indonesia and China.

It’s important to note that when we interact with different cultures, it is not about the absolute position but the relative position to each other. While the German culture is very explicit — especially when contrasted with an Asian culture, where communication highly depends on contextual cues — compared to North America, we are more subtle and do less to ensure that our message comes across clearly.

? ️Communication style: tactics for teamwork

If you have worked in a multicultural context, you have encountered differences in communication. Sometimes, they are subtle, and other times, they can have a bigger impact.

What I find generally helpful when working with new teams:

- Set communication and collaboration rules at the beginning of a workshop or longer working session (e.g., raise your hand before you speak).

- Start with a round of introduction, including personal communication practices (i.e. as a night owl, I am less communicative in the morning).

We are often unaware of our differences — because they seem so natural to us (doesn’t everyone think that way?). When communication challenges are happening during teamwork, I use one of the following facilitation techniques:

- active listening + validating: by repeating a message and seeking validation, you can support the team in gaining clarity

- making space: inviting participants with an implicit communication style to share more about their thoughts

- meta-discussion: pausing the teamwork and addressing communication challenges you’ve observed to allow the team to acknowledge and address the situation.

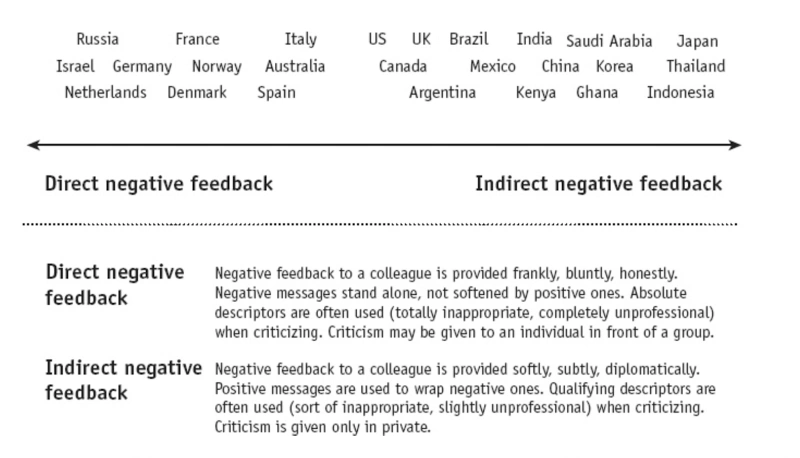

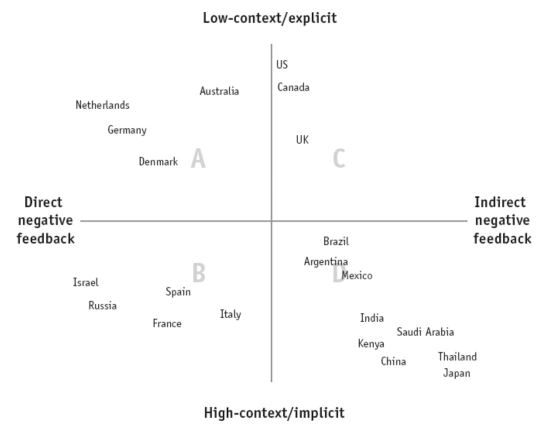

Providing feedback: direct vs indirect

There is a difference between being very explicit in one’s messaging and how we provide feedback or criticism. While feedback should be constructive, there is a range between a direct and diplomatic approach.

Cultures that prefer direct feedback share their criticism bluntly and honestly without softening it with positive messages.

Cultures that prefer an indirect feedback style share their evaluation softly and diplomatically, often wrapped in positive messages.

? Providing feedback: the cultural scale

Cultures that highly prefer a direct feedback style are Israel, the Netherlands, Russia, and Germany.

Cultures that prefer an indirect approach are Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, and Arabia.

This is also something I only realized once I moved abroad: the differences in giving feedback.

In Germany, I was very much used to receiving feedback directly, and I think of it as the most efficient way of communicating with each other (get to the point, forget the dance, tell me what you think). In Canada, I learned a different style: combining negative messages with positive ones, using the sandwich tactic.

I do have to say: while I like the “easing into sharing negative feedback,” there is often too much positivity and a lack of “real talk” for me. I prefer to grow and find myself growing best when I get direct feedback.

Notice that a general “communication style” differs from a “feedback style”. You can have a culture with an explicit but indirect feedback style (like Canada) or the opposite (direct feedback but implicit communication — like Russia).

? ️ Providing feedback: tactics for teamwork

Giving feedback is key in the design process. To create an open environment, I also find it helpful (just as for the communication style tips above) to start with some ground rules to set up a common feedback culture.

Regarding feedback, I often use the sandwich tactic: start with something positive, share something to improve, and end with something positive.

For longer teamwork sessions in a multicultural environment, you can also spend some time at the beginning to raise awareness of our communication differences:

- start your session by sharing some funny stories about different communication styles to remind everyone not to take anything personal

- start with an icebreaker exercise: share feedback scenarios and have people discuss the situation in small groups

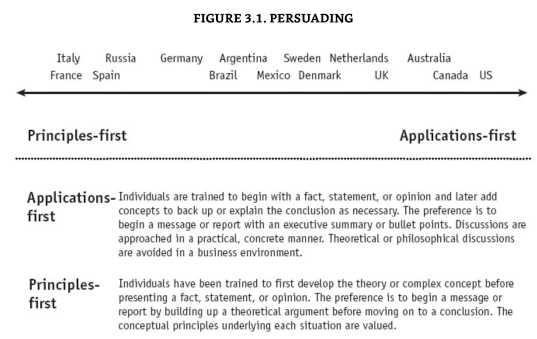

Persuasion: application-first vs principle-first

The way how we present, trying to get a message across and convince someone, can vary between an “application first” or a “principle first” approach.

Cultures that prefer a principle-first approach tend to start a presentation with a theoretical concept, the methods and principles that lead to a certain conclusion, before they share specific recommendations or a practical scenario.

Cultures with an application-first approach tend to present the opposite way: They start with a practical scenario that everyone can relate to (and often even skip the theoretical concept behind it).

? Persuasion: the cultural scale

Cultures that prefer the principle-first approach include France, Italy, Spain, and Russia.

Cultures with an application-f principle-first approachirst approach include the US, Canada, Australia and the UK.

I can relate to both approaches. While I enjoy the aspect of storytelling (which I think is increasingly important in our days of information overload), I think the best approach depends heavily on the context and the objective.

? Persuasion: tactics for teamwork

This is mostly relevant for you as a team leader and facilitator or in your role as a UX designer or researcher when communicating with stakeholders. The best tactics are:

- know your audience

- be aware of the different approaches and select the style you think is most appropriate

- try a mixed approach in a multicultural context

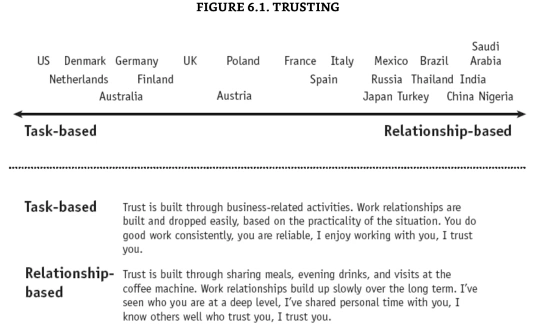

Trust: cognitive vs affective

Like communication, building trust is an important foundation for good teamwork and not an easy task for a facilitator. Erin found two extreme poles for trust building in groups: cognitive trust (task-based) and affective trust (relationship-based).

Cognitive trust comes from the head. It is built through work-related activities that provide insights into skills, reliability and accomplishments. Work relationships can be built (but also dropped) quickly.

Affective trust comes from the heart. Trust is built through relationships and activities outside of work, like sharing meals, laughing together, and sharing stories. Work relationships build up much slower, as it takes time to get to know each other.

? Trust: the cultural scale

More task-oriented cultures include the US, Netherlands, Denmark and Australia.

More relationship-focused cultures include Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, India and China.

Remember that this scale focuses on business relationships. While I do think that building long-lasting relationships always comes down to “the heart” and takes time, I see the difference in a work environment. In Canada, I find people are faster to collaborate with each other and welcome new people into the team than I am used to from Germany or Switzerland.

This might also be due to the aspect of friendliness. Erin uses the great analogy of peaches and coconuts. A peach culture (like Canada or the US) is often soft and friendly to people they have just met, but it’s hard to form deeper relationships (like in a peach, you will get to the pit quickly after breaking through the soft skin).

A coconut culture (like Germany) is not as open and friendly to strangers, but once you get behind the hard shell, you find the juicy inside and long-lasting relationships.

? Trust: tactics for teamwork

As a facilitator, it’s important to consider both dimensions and try to use a mixed approach.

- Trust-building exercises (like icebreakers) can work well for task-based cultures, but make sure to also include non-work-related activities (like drinks afterwards or a coffee break during).

- Give people the opportunity to work closely together by using small group activities.

Discussions: confrontational vs avoiding

Teamwork is all about creating an alignment and sharing thoughts. But how do you manage differences in opinions?

Confrontational cultures view disagreement as positive and fruitful. They embrace different opinions and separate a discussion from the overall relationship.

Cultures that avoid confrontation see disagreement as negative. It destroys a group’s harmony and can lead to “losing one’s face.”

? Disagreement: the cultural scale

Highly confrontational cultures are Israel, France, Germany and Russia.

Cultures that avoid confrontations include Indonesia, Japan, Thailand and Ghana.

Coming from a more confrontational culture, I personally struggle with this aspect repeatedly here in Canada. Confrontation doesn’t mean being aggressive — but it means being able to have different opinions and give room for argument. In North America, I see a big difference here, even within a country, between the East and the West Coast, with the West Coast being more avoidant of confrontations than the East Coast.

? Disagreement: tactics for teamwork

One of the main reasons for teamwork, especially in the design process, is to bring together all these different opinions and perspectives to achieve innovative outcomes.

As a facilitator, I find it important to work with the element of trust here as well:

- Create a safe environment for your group.

- Define ground rules for discussions and feedback.

- Facilitate discussions by either balancing out different opinions or drawing people out to share different aspects (or jump in with a devil’s advocate approach if you are working with a group that avoids confrontation).

- Bring the group to an alignment through voting exercises.

Over to you

As I stated in the beginning, trying to define a culture based on a few-dimensional scale oversimplifies our diversity. However, being aware of these simple concepts can help you better manage complex situations.

In your next meetings and workshops, try to be more aware of the different communication styles you see around you. Before you interpret or judge a message, consider these different elements: how else could you interpret the message? What can you do to improve the communication in your team? And what do you learn about yourself?

Happy growing ?